Eric Arthur from Cape Coast, Ghana, drives more than 100 miles in one weekend while driving around Ghana.

But Arthur is not a driver if you thought so.

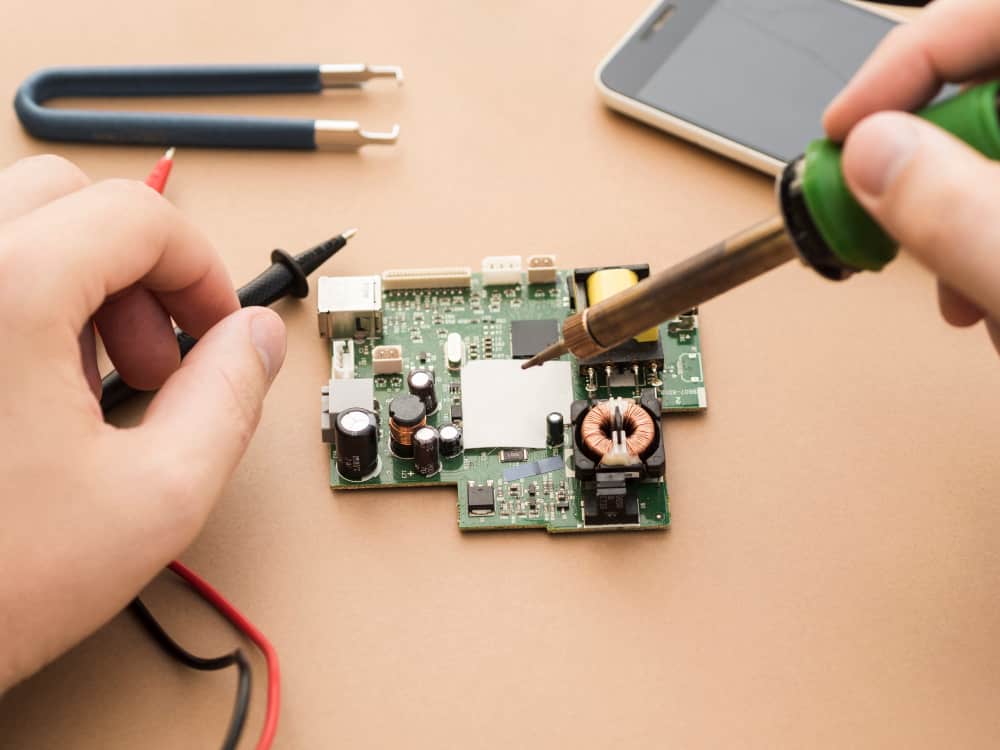

He collects broken phones from landfills or technical repair shops and collects about 400 broken cell phones in one weekend.

In addition to personally collecting them, Arthur coordinates six other people who are doing the same as him in other parts of Ghana, and he expects them to collect about 30,000 broken phones by the end of this year.

Arthur and his “employees” pay an average of 2.5 Ghanaian cedis for each broken phone, which is approximately $0.44.

Ghanaian entrepreneur says he often has to persuade people to sell him a phone that can no longer be repaired because it’s hard for them to separate themselves from, say, an iPhone they paid more than $150 for and sell it for a dollar or two.

Arthur and his agents are hired and paid for by the Dutch company Closing the Loop, which sends the phones collected by Arthur and his agents to Europe, where they are broken, recycled, and melted down in a specialized company.

The question is why broken phones are sent from Africa to Europe thousands of miles away?

Lucrative business

The co-founder of Closing the Loop, Joost de Kluijver, responds by stating there are no smelters in Africa specializing in the extraction of precious metals used in the manufacture of mobile devices.

Considering around 230 million mobile devices are sold annually in Africa, of which only 1% is recycled and most are discarded, it is clear this is a lucrative business with a number of environmental benefits.

When asked how they pay mobile phone collectors, De Kluijver says they are paid from the income that Closing the Loop generates from agreements with companies that pay Closing the Loop approximately 5 euros per mobile device.

Among the buyers of the phone are KPMG – a financial services company, but also the Dutch government.

The Environmental Impact of E-Waste Recycling in Africa

Despite recent efforts to establish ways to recycle e-waste in Africa, de Kluijver expresses skepticism about it, pointing out how without a clear legislative framework and a strong financial model, this goal is impossible to achieve.

Simone Andersson, a chief commercial officer of the Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Center – WEEE, which deals with electronic waste recycling in Kenya, says awareness and concern about the problem of recycling e-waste in Africa are growing.

Andersson points out that about 50,000 tons of electronic waste is generated annually in Kenya alone, and WEEE aims to establish collection centers across the country where people can leave their broken / unwanted electronics as well as build specialized smelters.

Achieving these goals, he adds, requires adequate infrastructure, and the Kenyan government is taking some steps to reduce and recycle e-waste.

Thus, the introduction of Extended Producer Responsibility legislation (EPR) is being discussed, according to which the responsibility for recycling electronic waste would lie with the importers of e-goods or manufacturers.

WEEE Center workers sort and disassemble electronic devices and recover some metals, such as copper and iron, while those that can only be recovered by specialized smelters – palladium, gold, and platinum, are sent to Europe.

De Kluijver points out Closing the Loop will help open specialized smelters in every way, but until then the only option is to send electronic waste to Europe.